Smarter Reinforcement Learning #

warning

- Disclaimer - used the freeCodeCamp.org and GH repo base code for the Snake Game

1 Introduction #

1.1. Background and Rules #

Blockade, a classic arcade game also recognized as Snake, debuted on the Gremlin platform back in 1976. Initially, it was exclusively accessible on consoles like the Atari 2600. However, its global popularity surged around the turn of the twenty-first century with its release on Nokia mobile phones. The primary objective of the game is to accumulate as many “apples” as possible within the confines of the board. Nevertheless, as the score escalates, the snake’s length increases, and the available space on the board diminishes, rendering navigation progressively challenging. The core rules of the game are as follows:

- The snake’s movement can be directed: up, down, left, or right.

- The snake always moves forward and increases in length by one frame (i.e., one pixel) after eating an apple. (Otherwise the tail in the stack is popped)

- If the snake hits its own body or the border of the board, the game ends.

- The position of the apples on the board is random, and there is only one apple present at any one time.

1.2. AI Interplay #

The Snake game typically presents two critical phases:

- Early game

- Late game

Initially, when the snake’s body is short and moves slowly, potentially leading to distractions and eventual demise, perhaps considered as not being challenging enough; and later, when fatigue sets in, player attention decreases resulting in the snake colliding with its own body or eventually getting stuck within its own boundaries, abruptly ending the game. These challenges are player-induced and a keyplay here is to introduc AI as it remains unaffected by emotional fluctuations and fatigue-induced errors.

To achieve this goal, a simple Reinforcement Learning (RL) approach was taken. Notably, successes such as Google’s DeepMind Challenge¹ in AlphaGo in 2017 mastering complex games have demonstrated the efficacy of RL. Hence, it can be seen that this is a commonly applied strategy to game-theory environments — training the AI to achieve higher scores in less time through RL.

¹ Google DeepMind Challenge Match with top-ranked Go player Lee Sedol.

But how to find the perfect solution?

Let us delve into the foundational concepts underpinning the most prominent scientific advances in RL algorithms.

1.3. Reinforcement Learning in Game Theory #

Arguably, over the past decade a lot of significant contributions have been made. DeepMind team’s utilization of the DQN algorithm on the Atari 2600 platform to surpass human-level performance levels. Subsequently, further advancements in RL algorithms for video games emerged.

For instance, Kevin Chen successfully employed DQN to play Flappy Bird. However, it was observed that with increased training sessions, overfitting occurred, leading to a gradual decline in the AI’s performance score.

Since then, both DeepMind and OpenAI have achieved remarkable success by applying RL algorithms to games like Starcraft 2. “This is how Google’s DeepMind crushed puny humans at StarCraft.”

Furthermore, there are numerous competitions, encompassing iterative deepening search, Monte Carlo Tree Search, Flood Fill and the A* algorithm, like the Micromouse Competition in Japan. Many papers and articles have emmerged in different topics for applied RL.

Motivated by these advancements, a study on the algorithms used was performed building upon the successes of previous endeavours. Further, hyperparameter selection optimization was also considered using a genetic algorithm.

2 Theoretical Foundation #

Following the previous section, a brief analysis of the suitability of the Snake game for RL methods was done focusing on the algorithms: Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Deep Q-Network (DQN).

The Snake game inherently embodies typical characteristics of a RL problem, making it well-suited for such algorithms. Firstly, the game environment is discrete and stationary (except in the case of multi-agent RL), as the snake can only navigate within a limited game window and can execute a finite set of actions. Secondly, at each time step, the state of the game is fully observable since the snake can perceive its surrounding environment and its own current state. Lastly, the primary objective is to maximize the game score, which translates to achieving the highest possible return.

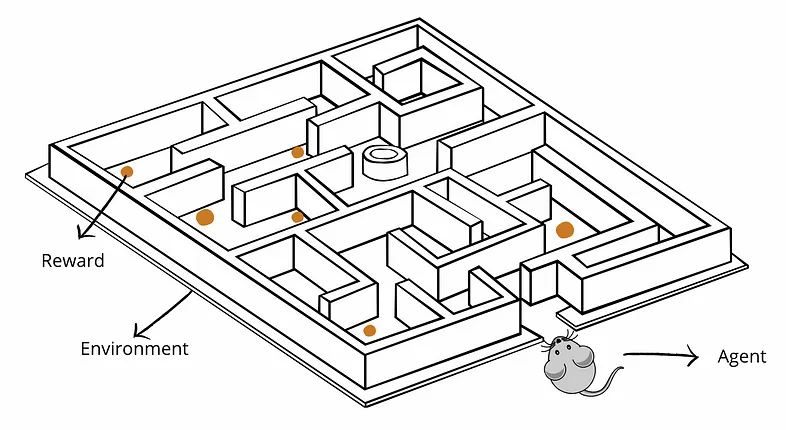

In the core, these algorithms function by enabling a machine learning model, or agent, to interact with the environment, learning optimal strategies to maximize returns. The agent operates by taking actions based on the current state of the environment and receives rewards accordingly. Through iterative learning, the agent attempts to optimize its decision-making process, aiming to maximize long-term returns by identifying the most effective strategies for action selection.

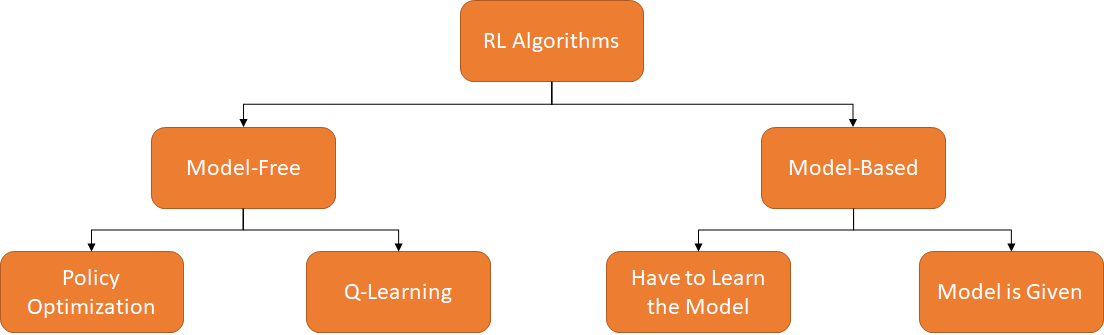

As per visualized, methods can be categorized into model-free and model-based approaches based on whether environmental models are utilized. Model-based algorithms involve the use of environmental models in decision-making, enabling the learning of dynamic laws and state transition probabilities to inform decisions. On the other hand, model-free algorithms learn strategies directly from experience without relying on pre-defined environmental models.

Both PPO and DQN algorithms fall under the model-free category. This is primarily because in many practical scenarios, the environment exhibits a large state and action space, making it challenging to accurately model its dynamics. Model-free algorithms alleviate this challenge by learning strategies directly from interactions with the environment, making them more versatile.

important

In the context of the Snake game, constructing a universal environmental model poses difficulties due to variations in the game window size and obstacle placement. Additionally, the discrete nature of states and actions in the Snake game necessitates extensive modeling and computation, resulting in high computational complexity for model-based approaches. In contrast, PPO and DQN algorithms utilize neural networks to approximate strategy and value functions, offering adaptability to different game maps and states with faster computation speeds. Hence, employing a model-free algorithm is more suitable for the Snake game.

3 Method Selection #

Based on the provided information, the lies on model-free algorithms, which can be categorized into policy-based and value-based approaches. The two widely-used algorithms from each category selected are: PPO and DQN, respectively, for separate experimentation.

Value-based algorithms, such as DQN, aim to learn an Action-Value Function (AVF) that predicts the long-term return of each action in every state. In the context of the Snake game, DQN can predict the expected return for actions. The agent then selects the action with the highest predicted return to maximize its score.

On the other hand, policy-based algorithms, like PPO, learn a policy function to directly select the optimal action in each state. In the Snake game, PPO learns a strategy function to choose the best action for maximizing returns.

In theory, while DQN excels in predicting action values and achieving stability, PPO outperforms in learning optimal policies swiftly and reliably, resulting in superior performance in the Snake game.

The PPO algorithm employs a strategy known as the “clipped surrogate objective” during training. This strategy, rooted in the concept of proximal policy optimization, aims to maximize strategy improvement while ensuring that each updated policy remains close to the previous one. Although effective in practice, this approach introduces randomness in decision-making.

In essence, PPO represents the strategy using a probability distribution during training and updates this distribution through sampling to enhance strategy refinement continuously. Consequently, decision-making during gameplay may vary due to the randomness inherent in each sampling process. Moreover, PPO incorporates an “exploration term” mechanism to promote exploratory behaviour within the strategy. This introduces randomness into the decision-making process, enabling the algorithm to explore new states and action combinations, thus avoiding over-reliance on existing experiences and facilitating adaptation to diverse environments.

While the randomness inherent in PPO aids in better environmental adaptation and helps avoid local optima, it can also lead to suboptimal decision-making.

4 User Controlled Snake #

For comparison purposes, initially a user-controlled Snake game was thoroughly implemented. Below, it is a detailed description of the core game mechanisms.

important

Most of the code for the game implementation was adapted using Pygame for providing a robust framework for game development in Python.

The code begins with initializing Pygame and setting up essential game parameters such as window size, colors, and game speed. Pygame’s functionalities are leveraged for window creation, event handling, and display rendering.

import random, pygame, sys, time

# Pygame initialization and window setup

check_errors = pygame.init()

if check_errors[1] > 0:

print(f'[!] Had {check_errors[1]} errors when initializing game, exiting...')

sys.exit(-1)

else:

print('[+] Game successfully initialized')

# Defined other variables here, adapt fontsize, window size, colors, speed,

# block size, etc...

In addition, SnakeGameUser and SnakeGameAI classes are defined which encapsulate the game logic, managing the game state, snake movement, collision detection, and food placement.

important

Vital functions encompass:

def __init__– Initializing game window and start up the game statedef _init_game– Initialize game state variables (snake position, score, food)def _place_food– Places food randomly within the game window, avoiding snake collisiondef _move– Handling snake movement based on user or AI actiondef play_step– Process each step of the game based on user (and later AI actions). (in addition, collects user input, move snake, check collision, update score, etc.)

Given __init__ and __init__game functions, the snake is initialized with a starting position, consisting of three body parts (self.head and two segments) positioned horizontally to the right - this is normally executed in good practice for developing a snake game, including representing the self.head at the center of the window. This setup essentially creates an initial length for the snake, allowing it to start the game with a visible length and direction. The snake initially consists of these three segments, and as the game progresses and the snake moves, additional segments will be added or removed based on its movement, food consumption, and collision detection.

tip

Having an initial length provides a visible presence of the snake on the screen, allowing the player or AI agent to see its position and direction from the beginning of the game.

def _init_game(self):

# Game state variables (snake position, score, food)

start_x = self.width // 2

start_y = self.height // 2

self.direction = Direction.RIGHT

self.head = Point(start_x, start_y)

self.snake = [self.head]

# Create initial instance of the snake with three blocks

for i in range(1, 3):

self.snake.append(Point(self.head.x - i * BLOCK_SIZE, start_y))

self.score = 0

self.food = None

self.frame_iteration = 0

self._place_food()

After snake initialization, the _move function adjusts the snake’s direction based on the received action (from user or AI). This is done using a list clockwise_directions that represents the directional movement of the snake - right, down, left, up (clockwise). Moreover, it determines the intended change in direction: no change, right turn, or left turn. Calculating the new direction index by locating the current direction within the clockwise_directions list and adjusting it based on the determined change, it then updates the snake’s direction accordingly.

note

Case scenarios: If the action indicates no change [1, 0, 0] -> snake maintains its current direction. If the action indicates a right turn [0, 1, 0] -> snake updates the direction to the next index in the clockwise order. If the action indicates a left turn [0, 0, 1] -> snake updates the direction to the previous index in the clockwise order (effectively, anti-clockwise).

Furthermore, using a dictionary movement_adjustments that maps directions for movement adjustments (changes in x and y coordinates), it applies the corresponding adjustment to the snake’s head position, effectively moving it in the intended direction by a distance specified by the BLOCK_SIZE, aligning its position with the game grid.

def _move(self, action):

# Define clockwise directions

clockwise_directions = [Direction.RIGHT, Direction.DOWN,

Direction.LEFT, Direction.UP]

current_direction = self.direction

# Define action codes for each movement direction

no_change_action = [1, 0, 0]

right_turn_action = [0, 1, 0]

left_turn_action = [0, 0, 1]

# Determine the change in direction based on action

if action == no_change_action:

direction_change = 0

elif action == right_turn_action:

direction_change = 1

elif action == left_turn_action:

direction_change = -1

# Calculate the new direction index

current_index = clockwise_directions.index(current_direction)

new_index = (current_index + direction_change) % 4

new_direction = clockwise_directions[new_index]

# Update the direction

self.direction = new_direction

# Define movement adjustments for each direction

movement_adjustments = {

Direction.RIGHT: (BLOCK_SIZE, 0),

Direction.LEFT: (-BLOCK_SIZE, 0),

Direction.DOWN: (0, BLOCK_SIZE),

Direction.UP: (0, -BLOCK_SIZE)

}

# Apply movement adjustments to update the head position

move_x, move_y = movement_adjustments[self.direction]

self.head = Point(self.head.x + move_x, self.head.y + move_y)

Afterwards, the _place_food selects a random position within the game grid to place the food for the snake. Initially creating a set containing all current positions occupied by the snake segments, it enters a loop that generates random x and y coordinates within the game boundaries, scaled by the block size, effectively aligning with the grid. These coordinates form a potential new food position. The loop continues generating random positions until it finds a position that doesn’t coincide with any segment of the snake. Once a suitable position is found, it assigns this new position as the food’s location, effectively placing the food at an unoccupied spot within the game grid, ensuring it does not overlap with the snake’s current positions.

def _place_food(self):

snake_positions = {point for point in self.snake} # set of snake positions

# Generate random positions until an available one is found

while True:

x = random.randint(0, (self.width - BLOCK_SIZE) // BLOCK_SIZE) * BLOCK_SIZE

y = random.randint(0, (self.height - BLOCK_SIZE) // BLOCK_SIZE) * BLOCK_SIZE

new_food_position = Point(x, y)

if new_food_position not in snake_positions:

self.food = new_food_position

break

For defining the game over condition, the is_collision function determines if a collision occurs at a given point within the game. Initially checking the point’s existence, defaulting to the snake’s head if not provided, it then examines whether the point lies beyond the game’s boundaries, assessing if its coordinates exceed the game area’s width or height. Additionally, it verifies if the point coincides with any part of the snake’s body, excluding the head. If the point is outside the game boundaries or matches a segment of the snake’s body, the function returns True, indicating a collision has occurred. Otherwise, it returns False, signifying no collision at that specific point in the game.

def is_collision(self, pt=None):

if pt is None:

pt = self.head

# Boundary collision check

collides_with_boundary = (

pt.x > self.width - BLOCK_SIZE or

pt.x < 0 or

pt.y > self.height - BLOCK_SIZE or

pt.y < 0

)

# Snake body collision check

collides_with_snake = pt in self.snake[1:]

return collides_with_boundary or collides_with_snake

Lastly, the play_step function manages a single step within the game loop. It increments the frame count to track game progress and handles events like quitting the game. It updates the snake’s movement based on the received action, adding a new head position to the snake’s body. In the case of a user-controlled snake game, it must take as input, the respective key that is being pressed at the time and adjust the action based on that specific task. Otherwise, play_step will take the action as an input value (in case of AI controlled).

def play_step(self):

self.frame_iteration +=1

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

pygame.quit()

quit()

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.key == pygame.K_LEFT:

self.direction = Direction.LEFT

elif event.key == pygame.K_RIGHT:

self.direction = Direction.RIGHT

elif event.key == pygame.K_UP:

self.direction = Direction.UP

elif event.key == pygame.K_DOWN:

self.direction = Direction.DOWN

Moreover, the function checks for game-ending conditions — such as collision with itself or exceeding a frame limit—and sets the game over status accordingly, applying penalties if necessary. If the snake consumes the food, it increments the score and updates the food position. After these actions, it refreshes the game display and controls the game’s frame rate before returning the reward earned, the game over status, and the current score, providing essential information for the game loop to proceed.

def play_step(self, action):

self.frame_iteration += 1

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

pygame.quit()

quit()

# Move the snake

self._move(action)

self.snake.insert(0, self.head)

# Check for game over conditions

game_over = False

reward = 0

collision_or_frame_limit = self.is_collision() or

self.frame_iteration > 100 * len(self.snake)

if collision_or_frame_limit:

game_over = True

reward = -10

return reward, game_over, self.score

# Check if the snake has eaten the food

if self.head == self.food:

self.score += 1

reward = 10

self._place_food()

else:

self.snake.pop()

# Update UI and clock

self._update_ui()

self.clock.tick(SPEED)

# Return game status and score

return reward, game_over, self.score